BILLY NAME (b. William George Linich, 1940–2016) was a photographer, lighting designer, and poet best known for “silvering” Andy Warhol’s Factory and for his photographs taken there between 1964–1970.

Photographs from Name’s Senior yearbook, 1958, Arlington High School.

Born February 22, 1940, Linich was raised in Poughkeepsie, NY. His father, a welder, was a member of the local ironworker’s union and his mother, Mary, was employed as a telephone operator. By the time he reached adolescence, Linich had developed an interest in literature and film, often hitching rides to nearby Vassar College on the weekends, to see Italian neorealist films and MGM musicals. When he was fifteen, he went to a tattoo parlor in New York City’s Chinatown where he picked out an image of a black panther which he had tattooed on his bicep. Sometimes he would attend drag car races in upstate New York or visit The Congress, Poughkeepsie’s only gay bar. Sometimes, he would take long walks around his neighborhood, gazing up at the massive expanse of the mid-Hudson Bridge which was repainted every seven-years with heavy duty-industrial aluminum paint. “I always thought of it as a sort of magic thing to do, paint a whole big thing all one color, silver.”

“I came out in 1958, in my senior year of high school. I told people I was a homosexual, even though I hated that word. I was just using it because it was available. Then I started thinking, “What is this genealogy we have with being heterosexual? Where do these archaic monstrosities come from? Where did these different names and categories come from, where you have to be one or the other?” I was gay because I had always been gay. It was such a relief to have it come into the public eye and have it be open, open, open until it was a blossom.” – Billy Name

Between 1954–1958, Linich attended Arlington High School in Poughkeepsie, located on Raymond Avenue. He excelled in his classes and was popular. So popular, that he was elected President of his senior class and was awarded the superlative “Most Versatile” in his senior yearbook. In his senior year, he would often take the train to the city with a girlfriend, Carolee Bell, and they would sleep on couches with Bohemian artist and musicians they befriended in Washington Square Park. They would hang out in Jazz clubs and explore a cultural scene that was far removed from the quiet life of Poughkeepsie. Shortly after graduation, in late summer or early fall of 1958, he and Carolee moved to New York City and got an apartment together. With a few dollars and a three-piece barber set gifted to him by his maternal great-uncle, Andy Gusmano, a barber in Poughkeepsie, Linich cut hair for extra money in addition to working part time as a waiter at various downtown restaurants. According to Gary Comenas, Linich described growing up as an "average repressed young American" until 1958 when he transplanted himself to Greenwich Village in New York City and “magically” became an occult artist.

Name in New York City, ca, 1963. Photo © Billy Name Estate

When Linch arrived in New York in 1958 at age eighteen, he was determined to make the city his home. An early acquaintance, the playwright Robert Heide, described Linich as, “an overgrown teenager, looking for someone to take him over and teach him something.” Linich picked up odd jobs and older men in hustler bars on the Upper East Side such as the Tick Tock and the 316. One of the men he picked up was the classical composer and musician Peter Hartman, who briefly became his boyfriend. Hartman introduced Linich to the poet Diane di Prima and, as a result, he gained entrée into the downtown arts, theater, and literary scene of which di Prima was a central figure. He and di Prima would remain close friends for the rest of their lives.

The founders of Serendipity 3, Calvin Holt, Stephen Bruce and Patch Carradine. Ca. 1960.

In 1959, Linich began working as a waiter at the legendary Upper East Side café boutique Serendipity III. Founded in 1954 by three gay men, Calvin Holt, Stephen Bruce, and Patch Carradine, the café fostered a campy atmosphere full of hodge-podge décor and Tiffany lighting, staffed by a cast of attractive young gay waiters. Warhol, who Linich had already met, was a Serendipity III regular and friends with its owners who were early supporters of his work and his 1957 financial records indicate that he spent just shy of $2,000 at the café that year (roughly the equivalent of $22,000 in today’s dollars). The year that Linich first met Warhol, he was still working as a commercial illustrator, most notably for the I. Miller Shoe Store and he would often sell the drawings that were rejected by his clients at Serendipity III. The two became close friends, attending art openings and going to the movies. They were also lovers off and on over the next 5-6 years.

Andy Warhol and Stephen Bruce (in doorway) of Serendipity 3. Ca. 1960.

Another important friendship that Linich developed at Serendipity III was with a fellow waiter named Ron Link, who would later become a celebrated off-Broadway director. Link introduced Linich to the social scene at the San Remo Café, a bar located at 93 MacDougal Street in Greenwich Village. There, Linich met the individuals that would soon comprise his inner circle of friends including Robert Olivio (better known as Ondine), and most significantly, the lighting designer Nick Cernovich. Cernovich had studied at Black Mountain College before moving to New York City where he became a sought-after lighting designer in the 1950s. At Black Mountain College, Cernovich was involved with the Light Sound Movement Workshop taught by Betty and Pete Jennerjahn between 1949 and 1951. The class focused much of their attention on creating short theater pieces using projected slides, painted backdrops, music and dance. (Harris, 208). The year before Linich met him, he had received an Obie (Off-Broadway) award for his lighting. In the 1950s, Cernovich had designed the lighting for some of downtown New York’s most experimental and avant-garde performing groups such as The Living Theatre, the Judson Dance Theater, James Waring, and Alvin Ailey. Linich became Cernovich’s apprentice and in exchange Cernovich became Name’s employer, teacher, lover, and guide. Name recalled, “It was the end of the period of the romantic avant-garde, the romantic bohemia, where artists kept younger artists and a male artist would always have a young man around.” Under Cernovich’s guidance, Name designed lighting for performances by Yvonne Rainer, Lucinda Childs, Merce Cunningham, Freddie Herko, and Diane di Prima for venues such as the Judson Memorial Church, the New York Poet’s Theater, and the Living Theater and his circle of friends and collaborators grew rapidly and exponentially between 1959 and 1962.

In 1960, Linich traveled as Cernovich’s assistant, to The Festival dei Due Mondi (Festival of the Two Worlds), an annual summer music and opera festival held each June to early July in Spoleto, Italy. Founded in 1958, by Gian Carlo Menotti, the festival sought to unite European and American culture and art. The 1960 festival took place from June 9 through July 10th, 1960. Prior to the festival’s opening, on January 9, 1960, The Waldorf Astoria Hotel in New York City hosted the Spoleto Festival Ball, a preview of some of the events scheduled for the festival, that took place in the hotel’s grand ballroom decorated to represent an eighteenth-century theatre. The entire ball was lit and directed by Cernovich with Linich as his assistant and performances that included entertainment by Odetta, the folk singer, Alvin Ailey and his dancers, Katherine Litz, David Vaughan, and a one-act play by Kenneth Koch produced by the Living Theatre.

Nick Cernovich, photographer and date unknown.

It was during this trip to Italy that Linich met Allen Midgette who described their first meeting “I was living in a park and when Billy walked by I fell out of the bush I was living in, landing almost on top of him.” Midgette, originally from Camden, New Jersey, was living in Italy, working as an actor in films by Pier Paolo Pasolini and Bernardo Bertolucci. He also had cameos in West Side Story and Cat People. Midgette would soon move back to New York and reconnected with Linich at the Factory, eventually starring in at least two Warhol films, Nude Restaurant and Lonesome Cowboys. He may be best known for impersonating Warhol on a college lecture tour in 1967. Later in life, Midgette and Linich both settled in the Hudson Valley and remained lifelong friends.

Allen Midgette on the set of Warhol’s Nude Restaurant, 1967. Photo © Billy Name Estate

In May 1962, a group of Fluxus artists organized the Yam Festival sponsored by the Spolin Gallery. For this festival, Linich created “The Billy Linich Show” a multi part performance that occurred over the course of the month and featured appearances by members of James Waring’s company. Gary Comenas notes, and the authors confirm, that reference is made to the “Billy Linich Show” in issue no. 26 of The Floating Bear, a mimeograph printed newsletter founded and published by Diane di Prima and LeRoi Jones. Issue no. 26 of The Floating Bear, which was published in October 1963, lists W. Linich as the “special guest editor for this issue, from the Billy Linich Show.” The issue contains contributions by Michael Katz, Kirby Doyle, Ray Johnson, two prose pieces titled “Dear Billy” and “Composition for W. Linich,” which contain gossipy campy tidbits about Linich and his social circle. The issue also notes the resignation of one of its editors, LeRoi Jones.

The front cover and two interior pages from The Floating Bear no. 26 published in 1962 which was guest edited by Billy Name.

"Billy was at that time doing a bit of everything: writing, collaging, taking odd combinations of drugs, making mots that sounded way hipper than they probably were, and mostly looking wise with a little half-smile and crinkly eyes." – Diane di Prima

During this period, Linich designed the lighting for an evening of performance organized by Philip Corner and Dick Higgins which included Higgin’s Two Generous Women, three renditions of La Monte Young’s Poem for Chairs, Tables, Benches, Philip Krum’s Lecture on Where to Go From Here, with sound by Corner, and Carolee Schneemann’s An Environment for Sounds and Motions. In 1962, Linich also designed the lighting for at least two concerts of dance for the Judson Dance Theatre group and in his free time, Linich also performed as a drone vocalist with La Monte Young and John Cage and through Young he met John Cale and Angus MacLise (pre-Velvet Underground). In his spare time Linich filled orders at Orientalia, a bookstore located at 11 E. 12th Street, managed by Cernovich that stocked hard-to-find books on Zen, Hinduism, Buddhism, astrology, and the occult. It was at Orientalia that Linich first began to develop what would become a lifelong commitment to Eastern Philosophy, the occult, and Buddhism.

At the end of 1962, Linich suffered severe burnout as a result of heavy amphetamine use and in February 1963, traveled from New York City to Diane di Prima’s house in Topanga Canyon, California to recover. When Linich arrived, di Prima was pregnant with her third child and she recalled him spending the majority of the winter months motionless on her couch.

“When he arrived at our door, he just looked ashen and gaunt – no doubt the effect of months of speed – and immediately took up residence on the living room couch. Alan [Marlowe] and I mutually took him on. We felt it our mission to bring him back to health. The only question was: how to manage it? . . . . We relied on Altadena Dairy to heal Billy. . . . Color began to come back into Billy’s face, and he spent more of his time sitting up on the couch instead of lying down. He began to tell the kids stories, and draw with Jeanne, and build the smoky fire in the evenings. So that when Michael Malcé and Freddie Herko arrived at our door ready for adventure, Billy was ready too. . . . He and Michael Malcé proposed that we all drive up the coast to San Francisco . . . . So Billy and I and the two kids climbed into Michael and Freddie’s rented car and set out . . .” – Diane di Prima

After arriving in San Francisco, the group stayed with Marilyn Rose in her home on the corner of Post and Laguna where Kirby Doyle and the poet Lewis Welch were also staying. After a few days, the group drove back down to Topanga Canyon, with the addition of Kirby and DeeDee Doyle in two cars. At this point it was almost Easter and di Prima hosted a large gathering at her house. Jim Elliot captured a photograph of the group.

Name (top left) in Topanga Canyon with Diane di Prima (holding Dominique “Mini” di Prima), Easter, April 14, 1963. Photo by Jim Elliot, courtesy Diane di Prima and Shepard Powell.

In the spring of 1963, sometime between Easter on April 14th and mid-May, Linich felt strong enough to return to New York City where he moved into an apartment at 272 East 7th Street in lower Manhattan and threw himself back into lighting design. He designed the lights for Concerts #6, #7, #10 in the sanctuary at the Judson Memorial Church which included original performances by Freddie Herko, Lucinda Childs, and Binghamton Birdie, aka Richard Stringer. In the program for this series of concerts, Sally Banes points out in Democracy's Body, “There is a small joke in the program credits that would only be apparent to someone who read all three programs. For Concert #6 it seems that Michael Katz was William Linich's ‘helper.’ On Concert #7, Linich was ‘aided by’ Katz. And on the third night, Concert #8, Linich was ‘supported by Katz.'” In June, he designed the sets for James Waring’s Pocket Follies. And, in August of 1963, Linich designed the lighting for a presentation of the Judson Dance Theater with performances by Lucinda Childs, Deborah Hay, Freddie Herko, Yvonne Rainer, and Arelen Rothlein. Very quickly, he fell back into his old downtown avant-garde social circle and shortly after returning to New York, spending a lit of time with sound and drone artist La Monte Young. Linich would spend hours and Young’s apartment morning with Marian Zazeela, Tony Conrad, Angus MacLise, John Cale and filmmaker Jack Smith, even occasionally participating in live public performances. He had not seen Warhol in a while but they reconnected through mutual friend, artist Ray Johnson, who invited both Linich and Warhol to the “Mr. New York,” bodybuilding contest at the Brooklyn Academy of Music on May 25, 1963.

Jill Johnston and Freddie Herko perform Pocket Follies at The New York Poet’s Theatre, June 10, 1963. Photo © Billy Name Estate

Linich’s apartment on the Lower East Side at 272 East 7th Street, became a central hangout for members of the downtown avant-garde art scene. As soon as he moved in he set out to create an environment that was all his own, eventually installing theatrical lights and painting the entire space silver.

“I had to discover the silver. I lived in a ramshackle Lower East Side apartment, so I thought I’d start putting some color in. I went to the local hardware store and got cans of spray paint—this was before everyone was using spray paint—and tried a red, a blue, a green: basic primary colors. But none of them really appealed to me. Then I saw a can of silver spray paint, and it just struck me as primeval, it had to be. So I got more cans of silver, and I did the whole apartment—the bathroom, the toilet, the refrigerator, everything.” – Billy Name

Billy Name cutting John Daley’s hair in Andy Warhol’s movie Haircut #1, filmed in Name’s apartment, 1963.

“It was like walking into a diamond, this great gem of a place. So I would be trimming somebody’s hair, and there would be like 125 people there—all the dancers, artists, and musicians. It was just a cool place to hang out.” – Billy Name

Every week, beginning in mid-1963, Linich would host a haircutting party where anyone was welcome to stop by to get a haircut and socialize, attracting artists, poets, dancers and musicians. These parties were made possible by the barber set that his uncle had given him and also offered a useful service to Linich’s community. In November of 1963, Ray Johnson brought Warhol and Gerard Malanga to Linich’s apartment for one of his haircutting parties.

“The lights were set so when Andy came in, he walked into a silver jewel . . . . I was cutting Johnny Dodd’s hair and it looked like it should have been a movie, of course.” – Billy Name

Warhol was so taken with the silver effect that he immediately asked Linich to transform the new studio for which he had recently signed the lease. Warhol also asked him if he could make a film about his haircutting parties and that same month, he filmed Haircut No. 1, a 24-minute film featuring John Daley, Freddie Herko, Billy Linich, and James Waring on six 100-foot rolls of film. Each roll was shot from a different angle, carefully framed with dramatic lighting designed by Linich. In quick succession, Warhol would make two additional films of Linich cutting hair in 1963, Haircut No. 2 filmed in the kitchen of Linich’s East Village apartment, and Haircut No. 3, filmed at the Factory where Warhol had moved his painting equipment into in November 1963, though the new space was still mostly empty.

“The magnetism that tugged at me was probably that silver world—that high-contrast black-and-white world—that I saw in the photographs shot at the Factory by a guy named Name, Billy Name. I wanted to live in those pictures and hang out with the stars: Edie Sedgwick, Viva, Taylor Mead, Ultra Violet, Baby Jane Holzer, Louis Waldon, International Velvet, Nico, Ondine, the Velvet Underground. It was a place where anybody who was somebody or in somebody’s entourage dropped in: the Stones, Dylan, Rauschenberg, Hollywood stars, Allen Ginsberg, and Jack Kerouac. It was the center of the hip universe, and nothing had ever looked like that before.” – Glenn O’Brien

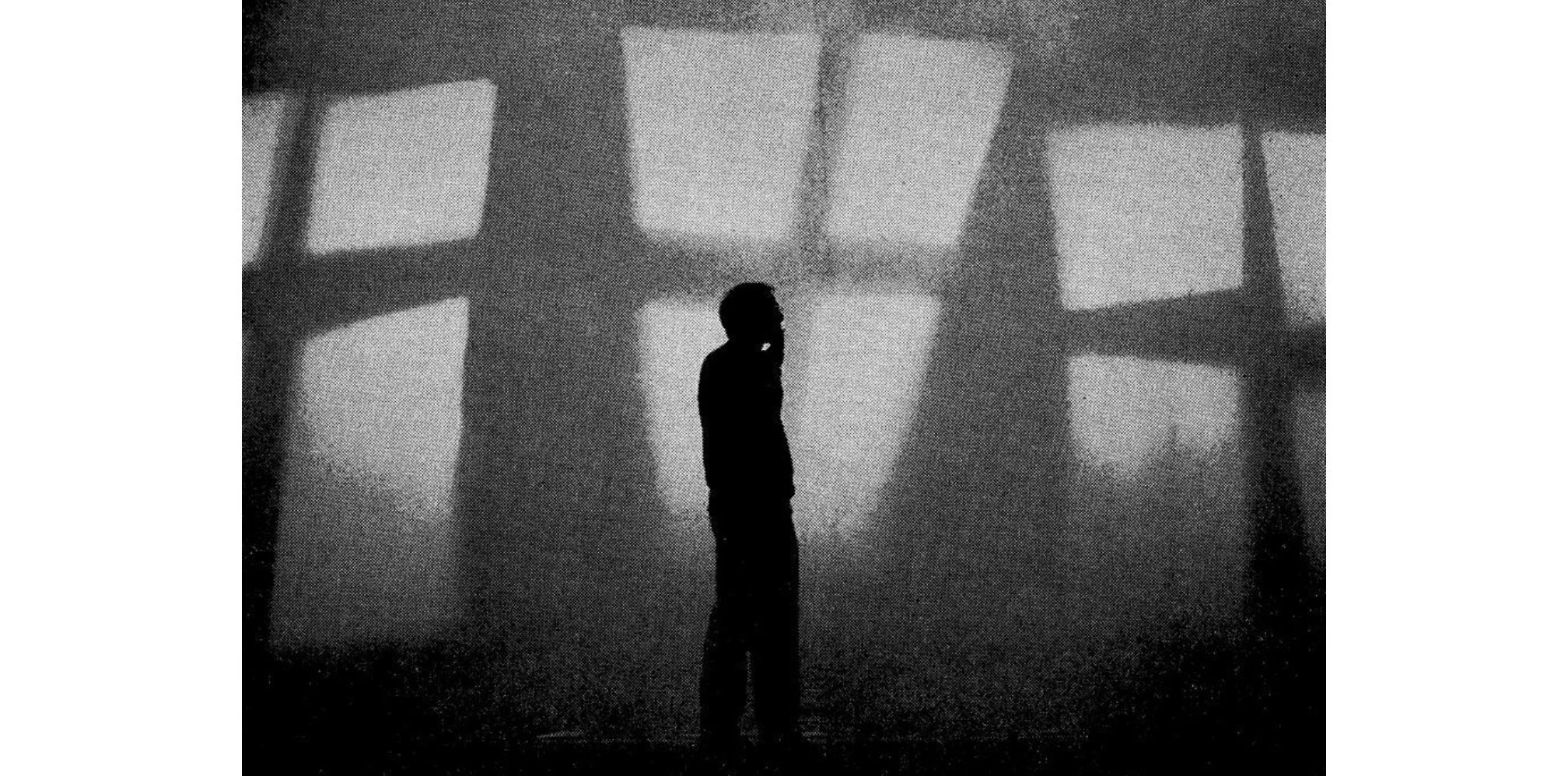

Andy Warhol’s 231 East 47th Street Factory. Photo © Billy Name Estate

"I picked up a lot from Billy actually-just studying him. He didn't say much, and when he did, it was either very practical and mundane or very enigmatic-like when he was ordering from Bickford's Coffee Shop downstairs, he'd be completely lucid, but if you asked him what he thought of something, he'd quietly say things like 'You cannot be yes without also being no.'" – Andy Warhol

Although Linich had visited Warhol’s new studio space in December 1963 to shoot Haircut No. 3, it was not until Monday, January 1, 1964 that he officially reported for work at 231 East 47th Street. Gerard Malanga was also there that day though they had previously met at one of Linich’s haircutting parties at his apartment the previous November. By this point, Malanga had been working for Warhol since June 1963 and in addition to Linich would become one of Warhol’s most important collaborators in the 1960s. Like, Linich, Malanga introduced a group of individuals and ideas to the Factory that would have otherwise been absent. Linich and Malanga, basically functioning as Warhol’s right and left hands, had an enormous impact on the trajectory of Warhol’s work, persona, and related ascension to fame. Warhol’s studio, which was his second studio after the fire station on 87th Street, was located on the fourth floor of the former Peoples Cold Storage and Warehouse, and had formerly, most likely, been an upholsterer’s shop that outfitted newly-made furniture. The raw space was about 50 feet deep and 100 feet long, one of the walls was brick and the ceiling had three arches. A bank of windows to the south offered the only available light for the raw space: the previous tenant had removed all of the light fixtures and exposed wires hung from holes in the ceiling, the floor was dirty grey concrete. The ground floor of the building was flanked by a parking garage and an antiques store. Warhol rented the space for $100 a year.

“In those days, in the avant-garde world, there was still the habit where older artists kept younger artists. The hetero artists always had a chick, and the gay guys always had a young guy with them. So when I first started being with Andy, it ended up that I was “his boy.” He was keeping me, even to the point where I moved into the Factory. When he started to become famous, we were doing so much work and were so busy. I mean, we really loved each other, and we got along great, but I wasn’t just this beautiful boy who wanted to be kept just for sex. So it only lasted until after I moved in. Then Andy got written up in Time, and all the attention that came with it just switched us over to a complete work relationship.” – Billy Name

Billy Linich at the Factory, 1964. Photo © Billy Name Estate

“The walls were cement and brick, and were crumbling, and the cement floors were crumbling and dirty. Andy started painting up by the front windows, because in the afternoons the sun came in there. You couldn’t see anything in the rest of the place because there was no electricity. There were overhead outlets but nothing in them, just dangling wires. The first thing that I had to do was install the lights. I went out to the local hardware store and bought these porcelain socket things, and put spotlights in.” – Billy Name

Linich immediately installed 300-watt general electric indoor-outdoor floodlights and spotlights bright enough for making art or making movies. Once the lighting was installed, he asked Warhol for a key so that he could work more flexible hours and avoid the long walk from the Astor Place subway to his apartment, and in late January Warhol gave him his own keys and Linich moved into the back northwest corner of the studio which would become his home for the next four years.

"Billy was responsible for the silver at the Factory. It was the perfect time to think silver. Silver was the future, it was spacey-the astronauts wore silver suits-Shepard, Grisson, and Glenn had already been up in them, and their equipment was silver too." – Andy Warhol

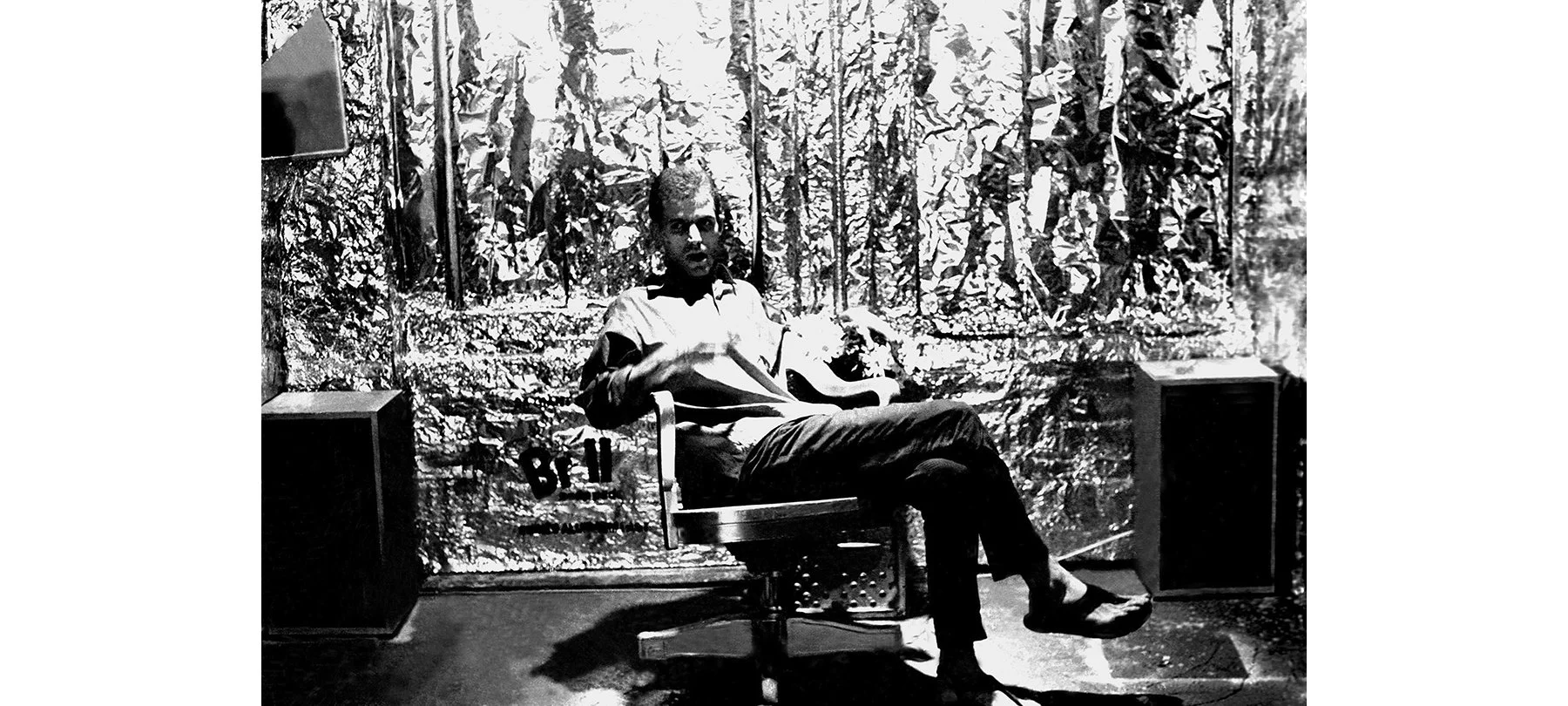

Andy Warhol at the Factory, 1964. Photo © Billy Name Estate

Drawing on his experience with stage and lighting design, Linich ordered four-by-eight sheets of 3/8 plywood, painted them silver, and hinged them together to create modular walls that could be used to hide his sleeping area and provide backdrops for Warhol’s films. He then began the enormous task of “silverizing” every square inch of the space. He began by attaching long rolls of Reynolds aluminum wrap to the walls and columns using glue and an industrial staple gun, then covering the water pipes and windows. He sprayed the floor and sections of the brick wall using DuPont Krylon paint. Linich also decorated with mirrors, some shards, some whole which he installed in the bathroom over the sink next to the film cabinets. Then, a work table for Warhol, a desk, wooden chairs on wheels – all of which he painted silver. Visitors would enter the Factory by boarding an old hand-operated freight elevator with a sliding grate and a small sign that read “Warhol-Linich.”

“At the old Factory (once a real factory), where the phone was a payphone painted silver, Name was the resident decorator, the majordomo, the receptionist, the bouncer, and occasional Warhol companion. The nucleus of the freaks who would become the superstars were Billy’s friends.” – Glenn O’Brien

Gerard Malanga, the Factory, 1964. Photo © Billy Name Estate

“It was like constructing this environment – for me, the whole place was a sculpture and each time I added a piece to it was like adding another gem to the collection. I never did a specifically articulated thing, I always did a maximal job. But it was the same art thing, it was the same signature, or my tag: the whole silver thing.” – Billy Name

Linich did not move into the Factory alone, he brought with him his two kittens, Ruby and Lacy, both of whom make appearances in several of his better known photographs from 1964.

Andy Warhol carrying a Brillo Box sculpture and Billy’s cat Ruby, 1964. Photo © Billy Name Estate

“The cats were mine. They moved in when I moved in. The previous year, I had taken in a stray calico cat from the sidewalk in front of my apartment. She nestled in the bottom of my closet, and then one day she had three kittens, and that’s when I found out she had been pregnant. As soon as she finished nursing, she took off and left them there. There was a black kitten, and a red kitten, and a grey kitten. I kept two, and I asked people if they wanted a kitten. Only Lucinda Childs wanted one. She took the grey one, which was named Gun because he was gunmetal grey. I kept the red one and the black one. They were named Ruby and Lacy, and I brought them with me when I moved into the Factory. They stayed for a while. But one morning Andy said, ‘Oh Billy! The cats are going to have to go, because they’re walking on the paintings!’ I had to convince Johnny Dodd to take them; he sent them to the orphanage in New Orleans where he had been raised. That was a very difficult scene. But the cats were quite the thing. They were in Eat with Robert Indiana and in photographs with Andy carrying the Brillo box. Ruby and Lacy are superstars!” – Billy Name

Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup box sculptures arranged in The Silver Factory, 1964. Photo © Billy Name Estate

“The idea was to create an installation composed of silver foil and silver paint. It was a maximal event, maximal meaning the opposite of minimal, it was a demonstration of covering all surfaces with a single coat of silver. I remember Reynolds Wrap heard about what I was doing and they sent a case of silver foil to the Factory. Surrounded in that space by all the silver, it felt like you were inside of a gem.” – Billy Name

It took Linich approximately half a year to complete the silverizing of the Factory. Its public debut as a total environment occurred on April 21, 1964, the evening of Warhol’s second solo exhibition opening at the Stable Gallery and the eve of the public opening of the New York World’s Fair. The Stable Gallery, established in 1953, was located at 33 East 74th Street and derived its name from its original location, a former livery stable on West 58th Street. Owned and operated by Eleanor Ward, the gallery gained a reputation for Ward’s dramatic, theatrical installations of post-Abstract Expressionist art. Warhol’s aptly titled second exhibition at the Stable, “The Personality of the Artist,” featured a large quantity of box sculptures and although very few works sold, people were lined up around the block to get in. At Warhol’s request, Linich designed the layout and installed the boxes in Ward’s gallery – boxes were piled high around the two-room gallery and visitors were encouraged to walk among them.

Andy Warhol’s box sculptures as arranged by Name, Stable Gallery, 1964. Photo © Billy Name Estate

“The day the show was going to open Andy asked me to go with him and arrange the boxes because he didn’t have time to do it. In the front of the gallery I arranged the boxes in a diamond pattern on the floor that you had to walk through to get to the back room. In the back room I piled them all up high, all the different boxes. I think they were priced at around $200 but Andy didn’t sell very many. Everybody liked them but no one really bought them.” – Billy Name

William S. Wilson’s description of the Stable opening, “It was the first circus opening, the first-gallery event.” The critic, Grace Glueck, wrote in the May 10, 1964 issue of The New York Times, “Is this an art gallery or a Gristede’s warehouse?”

Andy Warhol’s Brillo Box sculptures, Stable Gallery, 1964. Photo © Billy Name Estate

"Every time I see any of the boxes in exhibitions I can always spot the ones I painted because I was the most meticulous when it came to painting the rich even coat of white paint. When I was alone at night I would paint a lot of them and then the next day Gerard and Andy would neatly arrange the blank boxes into rows and silkscreen the colors on them." – Billy Name

On the evening of April 21, 1964, Marguerite Lamkin and Ethel Scull hosted the after party for the Stable show at Factory and had it catered by Nathan’s hot dogs. This party effectively launched the Factory as a new type of space, one that was quintessentially sixties and the evening thus marked a crucial turning point in Warhol’s career. Although Warhol would inhabit this legendary space which became known as the “Silver Factory” from 1964 to 1968, parties, especially public parties, were much less frequent than generally assumed and the perception of the Silver Factory as a public place is due in part to Name’s photographs which, in their exposure of the intimate, made what was a private and exclusive space, feel public.

"It was Billy Linich's energy and single mindedness that made the silver ambience - with his own two hands and always at night, or better in the wee hours, as Andy and the gang rarely left earlier than eleven or midnight. All the walls and surfaces were painted silver, or were papered with aluminum foil." – Henry Geldzahler, Former Curator, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Billy used a Honeywell H3 Pentax camera much like this one.

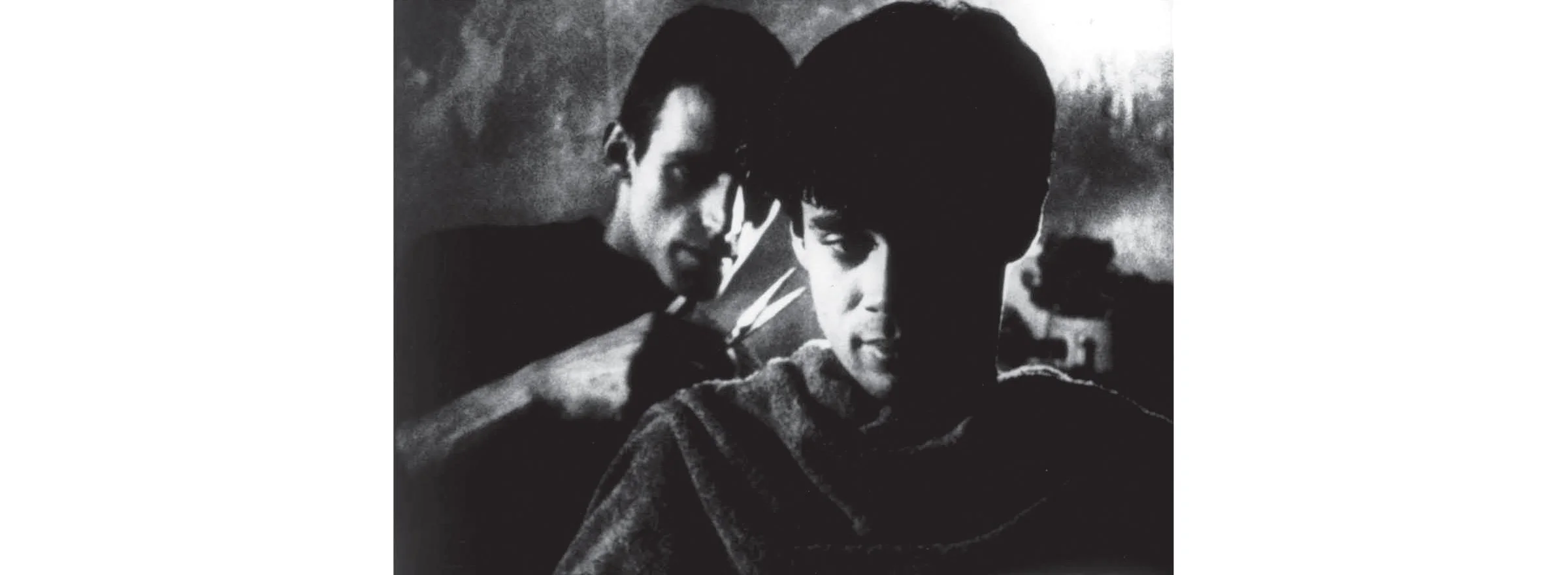

Jumping back in time for the sake of providing context, Warhol purchased a Heiland Honeywell Pentax H3 camera from Willoughby’s of New York on July 12, 1961, and after an unspecified trade-in, Warhol paid the balance of $162. The Pentax H3, known as the S3 everywhere but in the United States, was the fifth iteration of the original 1957 Asahi Pentax. The H3 offered a Fresnel focusing screen with a microprism spot in the center and it was completely mechanical and had quite a few quirks such as the way it was opened. It was also the first camera to feature a full auto diaphragm that allowed wide open focusing and composing and it was in production for two years. The very early examples had a max shutter speed of 1/500, but quickly changed to 1/1000. In short, it was not a camera for an amateur. It most likely sat around for a while, until sometime in 1963, Warhol gave Linich the camera. When Linich began working at the Factory, during the process of renovating the space, he converted one of the two bathrooms into his darkroom and with the camera’s manual, popular magazines, and some experimentation taught himself how to process film and develop prints himself. Although Linich lacked formal photography training, his background in stage and lighting design heavily influenced his unique dramatic style both in terms of how he framed his shots and also how he developed his prints. Linich’s position as Warhol’s closest Factory insider, coupled with his untrained photographic eye resulted in the most singular photographs ever taken of Warhol and his social scene in sharp contrast to the images created by many of the “trained” photographers that visited.

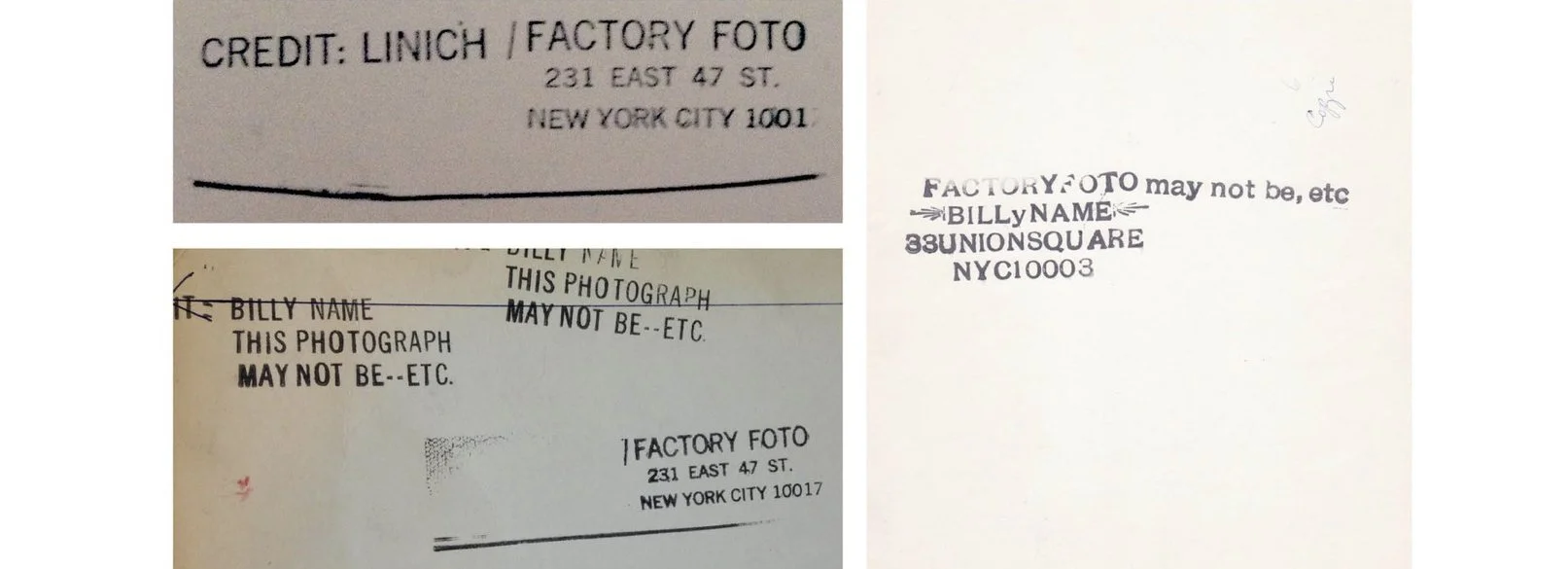

Billy Name’s original “CREDIT: LINICH / FACTORY FOTO” stamp (top) from the 231 East 47th Street Factory. He altered this rubber stamp when he changed his name, removing “CREDIT: LINICH” and adding a second “BILLY NAME THIS PHOTOGRAPH MAY NOT BE- -ETC.” stamp (bottom) to the back of his prints. A new stamp (right) was later made which combined both stamps when the Factory moved to 33 Union Square West.

It was at the Silver Factory, that Billy Linich reinvented himself and became Billy Name. This was to be one of the most important turning points in his life.

“We were doing some traveling with the Velvet Underground. When we would get back to the Factory I put one of the posters on the wall and it said Billy Linich. Billy Linich, that doesn’t look right to me, I was sitting at the desk, there was a form there. It said Name, I said ‘Name … Billy … Name. Hey that sounds great! Billy Name!’” – Billy Name

He would continue to identify as Billy Name for the rest of his life.

Gerard Malanga, 1965. Photo © Billy Name Estate

"The great thing about Billy's pictures is that you feel he isn't waiting to take the shot. He sees a moment, picks up his camera and grabs it. There's no hesitation in Billy's photographs because there is no hesitation in history. That's a very powerful feeling.” – Gerard Malanga

Name’s photographs of Warhol’s activities and the social scene around him through the 1960s serve as the most important documentation of an incredibly complex and important moment in cultural history.

“This accumulated exposure burned the images into the era’s consciousness as darkly glamorous icons of the 1960s avant-garde.” – Matt Wrbican, Former Chief Archivist of the Andy Warhol Museum.

In addition to being the resident photographer, Name was an essential part of almost everything that happened at the Factory, from acting as the resident DJ, spinning everything from Motown to Maria Callas to assisting Warhol and Malanga on the creation of paintings and sculptures and arranging paintings in groups that Warhol would then sell to collectors as Name had arranged. In addition documenting the mise-en-scène at the Factory, Name played an essential role in the creation and documentation of Warhol’s film practice both as on set photographer and lighting designer. During Warhol’s lifetime, Name’s photographs were originally used for publicity and published in almost every magazine or newspaper story about Warhol. They were also used for the film posters and press, most significantly for the international poster for Warhol’s film The Chelsea Girls.

Movie poster for Andy Warhol’s Chelsea Girls with Billy Name’s photograph of Warhol, Mary Woronov, International Velvet and Nico.

“The [still] photographs by Billy Name are an important part of the Warhol record and, in their framing of the filmmaking process, they acknowledge just how this process engaged the world view that perceives daily life and the individual’s imagination as raw material for film. The atmosphere of the Factory, the movement of the players, the development of the scenes, and the control of the action become clear in these photographs, as does the fact that Warhol’s presence and the Factory itself provided a life that extended beyond its walls and into apartments, theatres, and streets.” – John G. Handhardt, Curator, Film and Video, Director of the Andy Warhol Film Project, Whitney Museum of American Art

Name in front of his Warhol Screen Test and Haircut #2. These films were projected as continuous loops during his 2014 exhibition at MILK Gallery. Photo courtesy and © Michael Zagaris

When Name wasn’t shooting stills on the film sets, he sometimes appeared in the films, including (and in addition to the three versions of Haircut shot in 1963), Batman Dracula (1964), Couch (1964), 13 Most Beautiful Boys (1964–65), and an unreleased all male version of Nude Restaurant (1967). He also contributed off-screen dialogue, with Ronald Tavel and the poet Harry Fainlight, for the soundtrack of Warhol’s first sound film Harlot (1965) starring Mario Montez, and Lupe (1966) starring Edie Sedgwick. Name’s still photographs from the films were an especially important record, when Warhol removed his films from circulation in 1972, all that remained in public circulation through popular periodicals were Name’s photographs.

In 1964–65, Name and Warhol collaborated on a series of prints that were mechanically produced on the Thermofax machine that Warhol purchased at Name’s urging when he spotted the machine while shopping together in 1964. Gerard Malanga would also utilize the Thermofax machine to create a series of artworks based around his poetry with images from his personal collection which included images that Warhol had considered but rejected for his “Death and Disaster” series of paintings.

“A lot of the work is parallel to what Andy did because we both had the same resources. We both had the same file of movie photographs - some of which he selected for his images and some of which I selected for my images. For instance, the famous Marilyn Monroe paintings series was based on a specific photograph of Marilyn but I have a series . . . It is a series of Thermofax prints. 3M brought out one of the first copying machines and it was a thermal copy machine - a heat process. Andy bought it for me to use and to have something to play with. He would use it to . . . design works for his paintings. For instance, we did that with his flower paintings." – Billy Name

Al Hansen, Cafe Au Go Go, ca. 1965. Photo © Billy Name Estate

In 1965, Fluxus artist Al Hansen, who knew Warhol and Name (he photographed some of Hansen’s performances or “happenings”), introduced Warhol to his teenage daughter, Bibbe Hansen. She had recently spent time in juvenile jail and Warhol cast her in a film based on her experience called Prison. The film was shot at the Factory where Hansen starred alongside Edie Sedgwick, Pat Hartley, Sally Kirkland and Marie Menken. Hansen would shoot several other movies with Warhol including two Screen Tests. Hansen and Name would go on to be lifelong friends.

Bibbe Hansen and Edie Sedgwick on the set of Warhol’s film Prison, 1965. Photo © Billy Name Estate

"Billy wasn't an outsider come to shoot the outlandish denizens-he was one. Perhaps that is why his pictures remind me of family pictures. He was a family member documenting the tribe." – Bibbe Hansen

In 1966, Warhol began managing the music group The Velvet Underground and Name became close friends with the group, especially Lou Reed although he had met John Cale years earlier through La Monte Young. Name would photograph some of their performances dubbed “Andy Warhol’s Exploding Plastic Inevitable” and contribute photography to the band’s first three albums including the front covers for White Light/White Heat (1968) and The Velvet Underground (1969). Name is referenced in their 1969 song, “That’s The Story of My Life” in the lyrics:

That's the story of my life

That's the difference between wrong and right

But Billy said

That both those words are dead

That's the story of my life

The Velvet Underground during one of their Exploding Plastic Inevitable performances, 1967. Photo © Billy Name Estate

"Billy's stark photos have an unwritten wonder to them-they are the outward manifestation of the subject’s thoughts at that moment-fleeting, sudden, secretive, and full of energy." – John Cale

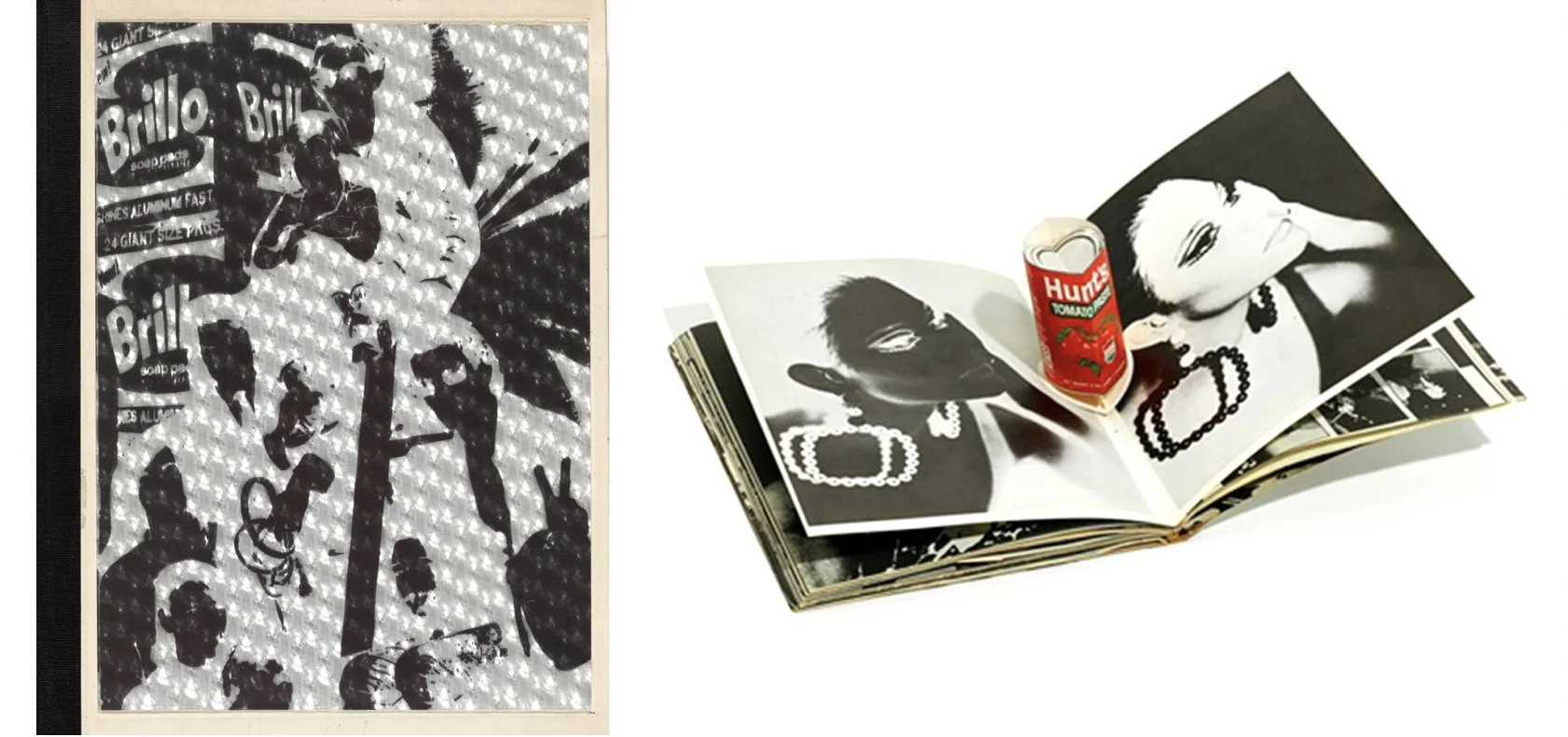

Andy Warhol’s Index, designed by Billy Name, 1967.

Also in 1966, Random House commissioned Warhol to create a book. Warhol tasked Name with overseeing the creation of what would be published as Andy Warhol’s Index in December 1967, though the title is generally known as “The Index Book.” Name designed the book alongside Akihito Shirakawa who was a well known children’s book designer, with help from Gerard Malanga. The Index book was based around the Factory inhabitants including Nico, Susan Bottomly (International Velvet), The Velvet Underground and Allen Midgette whose face appears in silver on the front cover of the softcover edition. Andy Warhol’s Index was like a children’s book for adults which included a lenticular cover, various pop-up elements including a whistling paper accordion, pop-up paper airplane, bound in record that could be removed and played, and other assorted complex paper toys. Nearly all of the photographs in the book are by Name with several additional photographs by Nat Finkelstein and Stephen Shore. Andy Warhol’s Index (Book) is now widely regarded as one of the most important mass produced artist objects ever created.

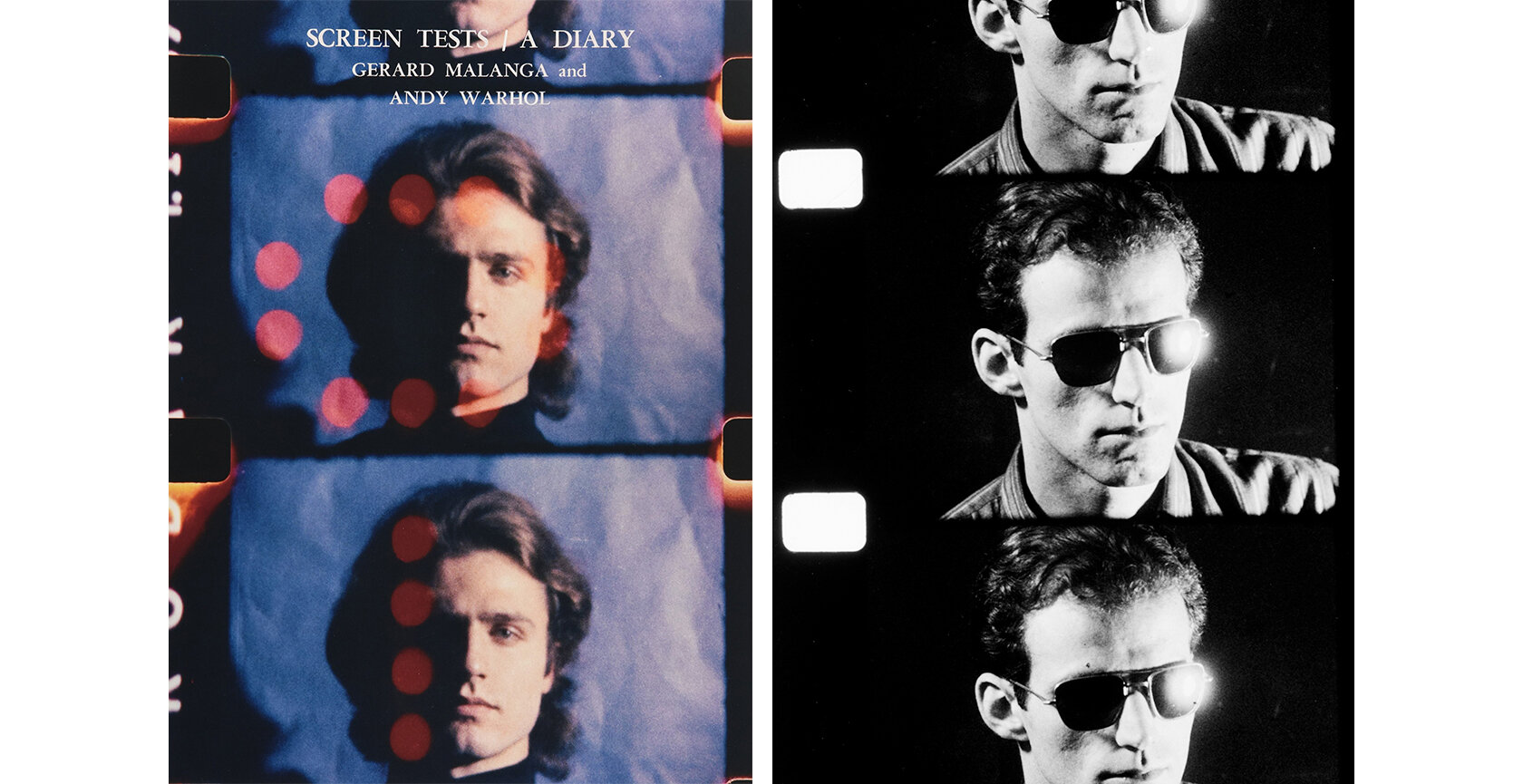

In 1967, Kulchur Press published the book Screen Tests/A Diary which was a collaboration between Gerard Malanga and Andy Warhol, pairing 54 of Malanga’s poems with 54 stills from the Warhol/Malanga Screen Tests, hand selected by Malanga. A still from one of Name’s Screen Tests appears in the book alongside the poem that Malanga wrote for him on August 28, 1966. An updated edition of the book was published in 2024 by The Waverly Press.

Billy Name Screen Test, 1966, from Screen Tests / A Diary, by Gerard Malanga & Andy Warhol, Copyright © 1967 by Gerard Malanga

1968, Name moved with Warhol to the new Factory which occupied the sixth floor of the Decker Building at 33 Union Square West and took up residence in one of the studio closets which also doubled as his darkroom. By this point, Warhol had moved away from painting and focused his energy on making films with director Paul Morrissey. To help promote his films Warhol started publishing Inter/View magazine in 1969 with help from John Wilcock and Gerard Malanga.

Larry Rivers, Susan Bottomly, Andy Warhol, and Billy Name (reflection) at the 33 Union Square West Factory, 1968. Photo © Billy Name Estate.

On January 30, 1968, the Velvet Underground released their second album, White Light/White Heat. The front cover art was an enlarged detail of Billy Name’s photograph of Joe Spencer and Ann Wehrer on the set of Warhol’s 1967 movie Bike Boy. The detail is Joe Spencer’s shoulder tattoo of a skull which Lou Reed discovered while looking through Name’s photographs. Billy Name enlarged, tilted and designed the cover to be printed light black on dark black so that the cover has to be tilted in the light to see the image.

The source photo for the Velvet Underground White Light/White Heat album cover, 1968. Photo © Billy Name Estate

In early 1968, Warhol gifted Name two Olympus Pen 35mm half-frame cameras. The shortened, narrow frame format meant that he could capture twice as many frames on each roll of film. A standard roll of 24 frames of 35mm film would now capture 48 frames. With this new camera, Name stepped away from his preferred black and white film and experimented with color film for the first time in earnest, shooting a large body of color photographs. Name further experimented with color photography by deliberately using the wrong chemicals to process the film which created unusual color effects and printed the color film in black and white which resulted in unusual gray tones that differed significantly from the black and white Kodak Tri-X film that he typically used. What’s notable with this body of color work is that Name stepped away from the Factory environment and shot people, objects and locations outside of The Factory, around New York City including Central Park, Max’s Kansas City, and various buildings and subway stations. Many of these shots were published in the 1997 book, All Tomorrow’s Parties.

Some of Name’s 1968 color photos. Ultra Violet, the 57th Street subway station, the building at the corner of 12th Street and Broadway and the Olympus Pen camera like the one Billy Name used that year. Photos © Billy Name Estate

In 1968, The Moderna Muséet in Stockholm published a catalog on the occasion of Warhol’s retrospective and first solo exhibition in a major museum. The catalog consists of three sections, a section of Warhol’s art, a section of photographs by Stephen Shore, and a section of approximately 200 photographs by Name. The softcover catalog was cheaply printed in black and white on coarse paper with cheap loose-leaf binding which caused most copies to degrade and fall apart in the more than five decades since its publication. The book was so popular that it went into three printings within two years.

Moderna Museet Stockholm catalog, 1968.

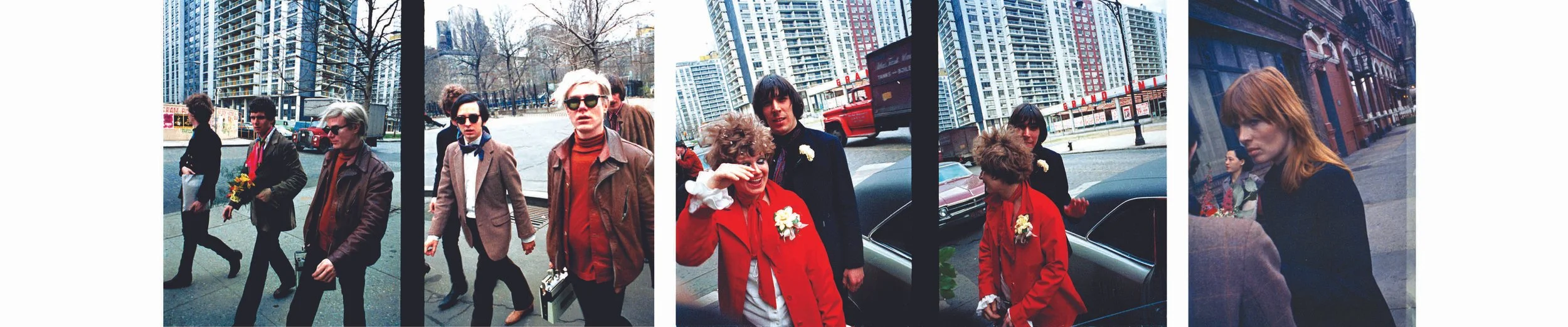

In April of 1968, with his new half-frame camera, Name took a series of photographs of John Cale and Betsey Johnson on their wedding day. The photographs were shot outdoors on La Guardia Place between Houston and Bleecker Street. The event was attended by Fred Hughes, Lou Reed, Viva, Paul Morrissey, Nico, and Sterling Morrison among others.

Betsey Johnson and John Cale’s wedding photos, 1968. Photos © Billy Name Estate

Also in 1968, Gerard Malanga included several of Name’s photographs in the “Monster Issue” of Intransit magazine that he guest edited in collaboration with Andy Warhol. This issue featured dozens of contributors including Søren Agenoux, Harry Fainlight, Jonas Mekas, Diane di Prima, Charles Plymell, Lou Reed and Allen Ginsberg.

On the afternoon of June 3, 1968, Name was working in his darkroom at the Factory when he heard what he thought were firecrackers being set off in the studio. Emerging from the darkroom, he found Warhol lying in a pool of blood, shot in the chest by the radical writer, Valerie Solanas who had fled seconds before in the elevator. Name cradled Warhol’s head in his arms and sobbed. He remembered Warhol said, “Don’t make me laugh, Billy. Please. It hurts too much.”

Valerie Solanas, Tom Baker and Gerard Malanga (left foreground) on the set of Warhol’s I, A Man, 1967. Photos © Billy Name Estate

Though Warhol survived this violent assault on his life, his health never fully recovered and the Factory became a dramatically different place. The attempt on Warhol’s life had a direct effect on Name’s actions which led to him taking fewer photographs. By 1970 he had virtually stopped taking photographs altogether. While he continued to live at the Factory, he withdrew socially and became committed to the study of astrology and Eastern and occult mysticism. He only permitted Lou Reed and Ondine to enter the closet he was living in. Everyone who worked in the Factory during the day rarely ever saw Name who would only emerge from his closet when Warhol asked him to take photographs or if a friend happened to visit. Name would only venture out at night after everyone had left and would work alone in the studio or go out to Max’s Kansas City and other Greenwich Village nightclubs with Lou Reed as his most frequent evening companion.

“Lou and I became especially close. From the moment we first met we bonded, it felt like we had known each other from childhood. He would often meet me at the Factory after everyone else had left and we would hang out in after-hours bars in the Village all night.” – Billy Name

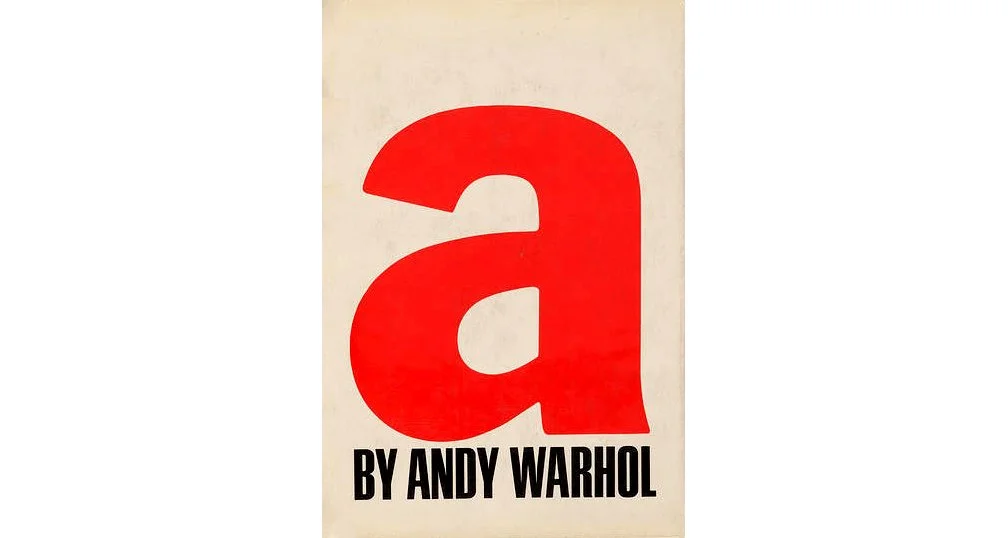

Throughout 1968, Name worked on editing the book a: A novel, which collects transcriptions of conversations between Warhol and Ondine taped between 1965-1967. The transcriptions were typed by Velvet Underground drummer Maureen Tucker and several high school girls who were hired to help finish the book. Name decided to preserve the typos, errors and even the format that each typist used to make the transcriptions. The title “a” was designated by Name who used it in reference to the heavy amphetamine use around the Factory in the mid 1960s, especially by Ondine during his taped conversations with Warhol. The book was published by Grove Press in November 1968.

a: A Novel, 1968.

“After Billy finished working on the galleys of a... ( A Novel) he went into his darkroom and didn’t come out... In the mornings we would find take-out containers and yogurt cups in the trash, but we never knew whether he went out himself at night to get food or whether some of his friends brought it in to him... but then one day Lou Reed came by and spent three whole hours in the darkroom with Billy. Lou came out regretting that he had given him three Alice Bailey books on witchcraft. Billy had shaved his head completely because he believed the hairs were growing in, not out - and was only eating whole-wheat wafers and rice crackers now - following the white magic book that shows you how to rebuild your cell structure.” – Andy Warhol

The Velvet Underground, the Factory, 1969. The image on the right was used on the cover of their self titled album that same year. Photos © Billy Name Estate

In 1969, Name took at least two groups of color photographs of the Velvet Underground at the Factory with their new member, Doug Yule who replaced the recently departed John Cale. One roll of film was processed normally while the other appears to have been an experiment in cross processing which created a psychedelic effect. One of the photos was selected for the cover of their upcoming self titled album which was reproduced in black and white.

He (Billy) is part of the Factory. He does all our covers. He's a divinity in action on Earth. He does pictures that are unspeakably beautiful. Just pure space. For the people who have one foot on Earth and another foot on Venus, they would like that kind of picture because it's out-and-out space." – Lou Reed

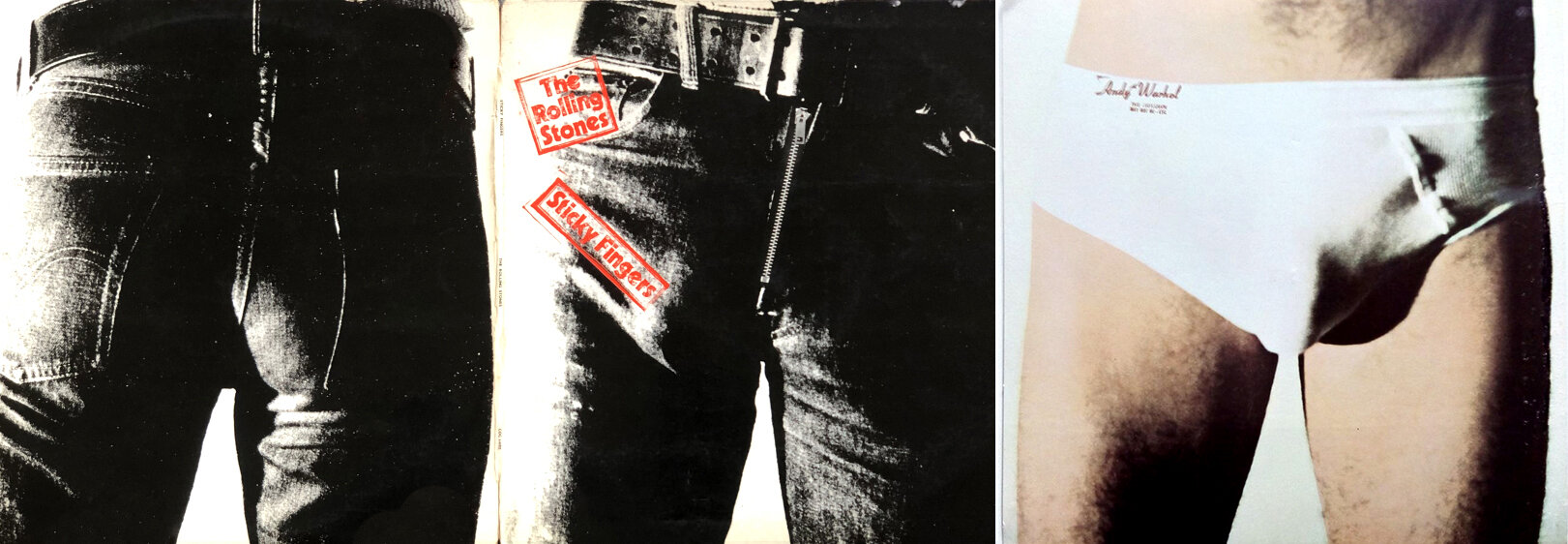

The Rolling Stones album cover for Sticky Fingers designed by Andy Warhol with photography credited to Billy Name.

In 1970, Andy Warhol was commissioned to design the cover for the album Sticky Fingers by The Rolling Stones which was released the following year in 1971. Warhol shot numerous Polaroid studies for the cover, and directed Billy Name to shoot similar photographs on 35mm film. Warhol routinely tasked Name with shooting work for him as the resident Factory photographer. Name and Warhol photographed various Factory visitors in tight jeans and underwear for the cover including Glenn O’Brien, Cory Grant Tippin, Joe Dallesandro, and others, though the person wearing the jeans in the shot that was used for the final cover was never definitively confirmed by Warhol. By his own account, Name remembered taking the photographs alongside Warhol but could not recall which model was selected for the album cover or whether his or Warhol’s shots were utilized, though Name is widely credited as the photographer. Glenn O’Brien later recounted that his underwear shot was used, recognizing the underwear printed on the inner sleeve as his own. He also recalled that Warhol paid him $100 for use of his photo. Corey Grant Tippin recalled in an interview that he was paid $75 by Warhol for use of his jeans shot on the front and back of the album sleeve. Printed on the undergarment under Warhol’s signature stamp on the inner sleeve is Name’s own stamp “This photo may not be - etc…” the same stamp that he would apply onto the back of his own Factory photographs, also known as “Factory Fotos.” Use of this stamp may be the only surviving evidence of Name’s involvement in the album art. Though the mystery around this cover endures more than five decades later, Tippin and O’Brien are the likely models. Designer Craig Braun executed Warhol’s final design which included a real working zipper on the front cover, cementing its place as one of the most innovative and memorable album sleeves of all time.

Name’s goodbye note to Warhol when he left The Factory in 1970 or 71.

“I didn’t give anybody a chance to react. I just left a note on my darkroom door.” – Billy Name

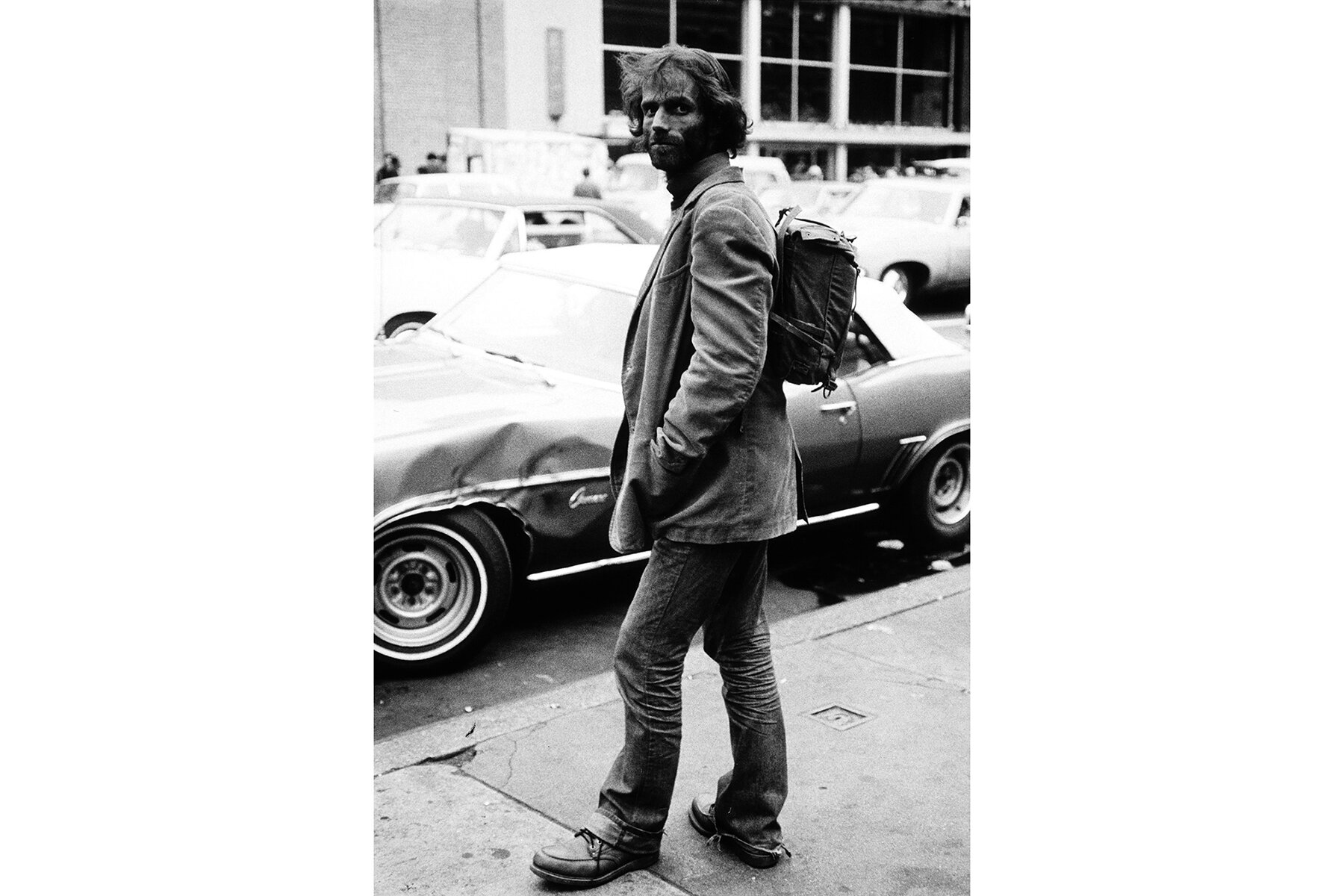

The date of Name’s departure from The Factory isn’t definitively known, with most accounts putting the date at sometime between late 1970 and early ‘71. Name himself could not remember exactly when he left and historically went along with anyone else’s account. Vincent Fremont recalls Name departing in early 1971, shortly after he returned from an extended stay in Los Angeles. This is the date that we recognize unless we come across any other clear evidence supporting another date. Late one night, Name walked out of his closet, tore a page from an art catalog on Warhol’s desk and with a red marker wrote “Andy - I am not here anymore but I am fine Love, Billy.” He taped the note to the door and left forever. Vincent Fremont recalled that the next day, at Warhol’s direction, he packed up all of Name’s possessions into his silver trunk including the thousands of frames of film he had shot over the previous decade, photographic prints, star charts, occult books and tarot card decks. Billy’s cameras were also packed in the trunk but disappeared sometime before the truck and its contents were returned to Billy when Warhol passed away in 1987. When Name left the Factory, he moved in with a friend in U.N. Plaza who was a diplomat from South America. Some time later, Gerard Malanga ran into Name on the street and took a photo of him as he was starting to grow his trademark beard that he would wear for the rest of his life. When Name left the Factory, he took with him a large group of paintings that Warhol had gifted to him over the years including several flower paintings and a Jackie triptych. These paintings were left with his friend Henry Geldzahler for safe keeping until his eventual return. Most, if not all of them were personally dedicated to Name on the back by Warhol, dedicated either “To Billy” or “For Billy.”

Billy Name, 1971. Photo: Courtesy and © Gerard Malanga.

"I went off by myself and spent a lot of time being very hermetic…" – Billy Name

After a few weeks of living at U.N. Plaza, Name befriended a group of young people in Washington Square Park and accepted their invitation to work on a fruit and vegetable farm in Georgia, on the way they stopped in Washington D.C. where he witnessed the demonstrations against the Vietnam War. From there, Name spent the next several months working on farms in Georgia and Florida, then hitchhiking west, stopping and spending time in New Orleans, Houston, and Boulder. Name eventually made his way to San Francisco, landing at the front door of Diane di Prima’s house in the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood. He was physically and spiritually exhausted and di Prima once again nursed Name back to health. She recalled that he had saved her life years earlier, and that she saved Name’s life twice.

"I’ve known Billy a long, long time.... he showed up at another house I had, to recover from years of Andy. It was around 1970, I think, after the Holy Ghost had told him to leave Andy forever. That was when he left everything behind. He was completely out of his mind. He read the same page of the same book for several months: page thirty-seven of Esoteric Astrology by Alice Bailey. He would see things in the air and he would catch them. This went on for months and months." – Diane di Prima

Esoteric Astrology by Alice Bailey.

After several months living with di Prima and her family, Name moved into an SRO in San Francisco’s North Beach neighborhood near the edge of Union Square where he spent most of the 1970s looking inward and reflecting on his life. This included spending long hours meditating on the shore of Ocean Beach at the edge of the city. Through the process of this deep spiritual self-reflection he discovered concrete poetry and conceptual sculpture. Name’s friend Gerard Malanga spent much of 1972-73 in San Francisco and the two friends crossed paths several times during this period including at a screening of Malanga’s 16mm movies which Name attended. Name generally had little to say about his time in San Francisco other than he loved the city, but this period of his life remains a mystery.

“Once I got out into the world and real life, things became deeper and more serious and even tragic at some points. Out in the real world where I wasn’t protected by the walls of the Factory, I had a lot of tragic things happen simply because life is tragic.” – Billy Name

In 1977, Name left San Francisco and returned to Poughkeepsie, NY, reestablishing his New York connections with Warhol and Henry Geldzahler. When he asked Geldzahler about getting back his Warhol paintings he was informed that they had all been stolen by Paul America and were never recovered. Name went back to school, earning his degree in business administration and in 1986, he started the Mid-Hudson Arts & Science Center, continued writing poetry, and developed a co-op with artists from the mid-Hudson area.

Popism, 1980.

In 1980, Warhol used many of Name’s photographs to illustrate his memoir of the 1960s, POPism in which he wrote:

“The only things that ever came even close to conveying the look and feel of the Factory then, aside from the movies we shot there, were the still photographs Billy took.” – Andy Warhol

Andy Warhol died on February 22, 1987, Name’s 47th birthday. As Name recalled, “I sat in a chair and cried all day.” After Warhol’s passing, Warhol’s executor Fred Hughes contacted Name and reminded him that Warhol had saved his silver trunk full of photographs, star charts, books, tarot card decks and everything else he had left behind 17 years prior. Vincent Fremont returned the property to Name on the order of Warhol’s estate. Fremont later recalled that Warhol took extra care to preserve Name’s possessions and silver trunk for the day they would be returned to him. Name had found the beat up old steamer trunk in the basement of the Factory’s building in 1964 and had painted it silver. After being reunited with his belongings and film from the 1960’s, Name started spending time in the darkroom again and through the 1990s experimented with developing techniques, refining his high contrast style he first developed in the 1960s. Most, if not all of the prints he produced during this period were 11x14 RC-Type prints. Name also began to produce new works of conceptual photography and sculpture and continued to develop his Aerial Canon of Concrete poetry which is based on the vowel system and was, for Name, a way of transforming energy into the form of vocalized sounds which connect back to his days as a drone vocalist in the early 1960s.

Songs for Drella album cover.

In 1990, Lou Reed and John Cale used a photo of Warhol by Name superimposed over their faces on the cover of their album Songs for Drella. They reference Billy Name in the lyrics to the song “A Dream” which is a spoken word piece by Cale told from the perspective of Warhol over hauntingly minimalist music.

In 1992, The Velvet Underground reunited and Lou Reed invited Name to travel with them on their European tour and take photographs. John Cale recalled in his foreword to Billy Name: The Silver Age, “on what would be one of the last meetings with the VU – a European jaunt at the behest of the Cartier Foundation in Paris. We traipsed across Paris . . . we could see Billy’s influence on each of us – in my case, I noticed how his keeping close to Lou was part of an exercise in mind reading as he played the role of human tranquilizer for our fraught meetings and meals . . . . it was eventually easy to notice how every time we met without Billy, the trepidation grew and we slipped back into coitus interruptus style of conversation. Then Billy would join us and we all relaxed…”

Also this same year, Prestel published the book Billy Name, Stills from the Warhol Films, collecting stills and contact sheets of Name’s photographs on the sets of Warhol’s movies during the 1960s.

Several sequences from Name’s 1996 Photo Booth collaboration with artist Blake Boyd. Photos © Blake Boyd

In 1996, Name collaborated with Louisiana-based artist Blake Boyd on an extensive series of Photo Booth portraits where Name portrayed well-known pop-culture figures including Colonel Sanders, Burger King, Santa Claus, and Yosemite Sam, in addition to capturing performative actions such as Name “silvering” himself. Name considered this series to be one of his most important contemporary artistic collaborations.

Also in 1996, Name was introduced to Dagon James by mutual friend, photographer Leee Black Childers. Name and James would strike up a lasting friendship that eventually led to James becoming Name’s publisher in 2004 and eventually his agent and archivist in 2010..

Name’s books Stills from the Warhol Films, 1992, Factory Foto, 1996 and All Tomorrow’s Parties, 1997.

In 1996, the Japanese gallery, Parco, organized an exhibition of Name’s photographs and published a monograph in conjunction with the exhibition titled Factory Foto. Inspired by the format of the 1968 Stockholm catalog, the catalogue contains Name’s Factory photographs reproduced in Name’s signature high contrast style on uncoated paper.

In 1997, frieze, London and D.A.P., New York with generous support of the Arts Council of England published All Tomorrow’s Parties, a monograph featuring Name’s color photography, primarily from 1968. The publication also included an essay by Dave Hickey and an interview with Name by Collier Schorr.

Lid magazine issues 4, 14 and 17 with covers by Billy Name.

In 2004, Name began collaborating with Dagon James as a contributor to James’ recently launched Lid Magazine and would contribute on a regular basis starting with issue #2 until its final issue, no. 17 in 2014. The final issue featured an interview with Name conducted by the magazine’s London editor Dave Brolan, with a photographic tribute to his friend Lou Reed who had recently passed away.

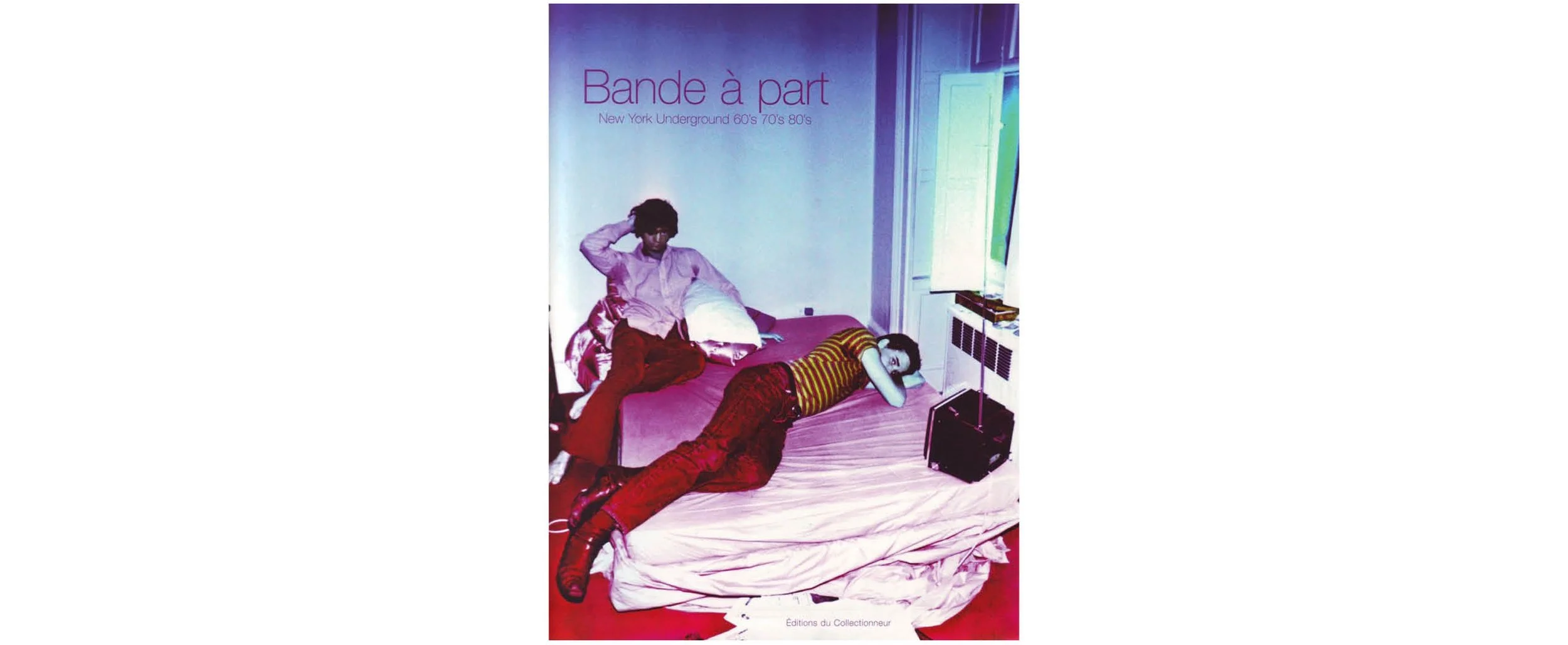

Billy Name’s 1968 photograph of Cory Tippin and Jay Johnson on the cover of the 2005 exhibition catalog Bande à part.

In 2005, photographer Roberta Bayley curated the exhibition, Bande à part: New York Underground 60s, 70s, and 80s, sponsored by Agnes. b. The exhibition included many of Name’s friends and contemporaries including Gerard Malanga, Leee Black Childers, Danny Fields, Anton Perich, Godlis, Bobby Grossman, Bob Gruen, Maripol, Marcia Resnick, and Stephanie Chernikowski. The Bande à part exhibition traveled to London, Paris, Tokyo, Hong Kong, Los Angeles, Portland, and closed in New York City at the Clic gallery in SOHO. Name’s 1968 color photograph of Cory Grant Tippin and Jay Johnson was reproduced on the front cover of the accompanying catalog which included 14 of Name’s photographs in the book interior.

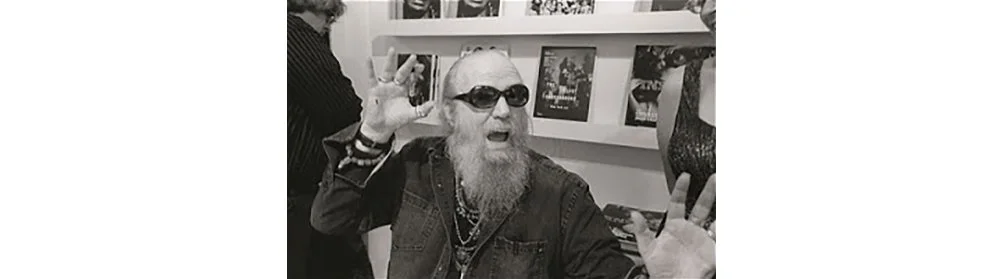

Billy Name at Clic gallery. Photo: Courtesy and © GODLIS

"I'm very much interested in portraiture, not only of people but of spaces. I was interested in using angles to make the structure evident, like looking at form in an abstract painting…" – Billy Name

In 2010 Name invited Dagon James to be his agent full-time and oversee all licensing, publishing and archivist duties. The two immediately embarked on a comprehensive book of Name’s photographs that had first been discussed between them in 2005 in addition to numerous other projects.

Billy Name and Gerard Malanga at Name’s opening in Rhinebeck, 2011. Photo: Courtesy and © John Duke Kisch

In 2011, Name had an exhibition of his photographs on view at Shahinian Fine Art in Rhinebeck, New York. The prints in this exhibition were the same prints that were on view in the Pompidou Museum the previous year. The opening was attended by many of his friends and colleagues in the region including Gerard Malanga and John Duke Kisch.

Name in a still from the film Becoming Billy Name directed by Alexa Karolinski, 2012.

In 2012 Name collaborated on the 14-minute film called Becoming Billy Name which was co-produced by Alexa Karolinski and Dagon James and directed by Karolinski who later went on to co-create and co-write the Emmy Award winning series Unorthodox for Netflix. Much of the film is centered around Name’s current creative output and his life as a practicing Buddhist living in Poughkeepsie. The film can be viewed on the video page of this website.

The opening reception for the Andy Warhol’s 13 Most Wanted Men exhibition at the Queens Museum, April, 2014. From left: Barbara Moore, Sean Carrillo, Billy Name, Bibbe Hansen, Anastasia Rygle and Dagon James.

On October 30, 2013, Name invited James to accompany him to Jane Holzer’s New York City house where he was to be interviewed by Andy Warhol Museum director Eric Shiner for the catalog for the upcoming exhibition “Andy Warhol’s 13 Most Wanted Men” at the Queens Museum. Accompanying Shiner was curator Anastasia Rygle who was organizing the exhibition and catalog. Name contributed photographs to the exhibition which opened in April, 2014, and several months later Rygle agreed to help Name and James edit and complete their upcoming book, The Silver Age.

The end of the night group photo from the Andy Warhol Museum 20th anniversary gala, May, 2014. Billy Name is in the back wearing sunglasses.

In May, 2014, Billy Name attended the 20th anniversary gala at the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh which had numerous photographs by Name on view throughout the museum. This was Name’s final trip outside of New York.

Also in 2014, John Cale prominently featured Name’s photographs in the music video for his new song “If you were still around” which can be seen on the video page on this site.

Billy Name: The Silver Age, published in 2014 by Reel Art Press.

In November 2014, Tony Nourmand, of London based imprint Reel Art Press published Billy Name’s book, The Silver Age. The book brought together most of Name’s subjects and friends from the 1960’s including Allen Midgette, Danny Fields, Diane di Prima, Viva, Mary Woronov, Robert Heide, Brigid Berlin, Bibbe Hansen, Allen Midgette, John Cale, Glenn O’Brien and Gerard Malanga who contributed their personal experiences around Warhol’s 1960s Factory alongside Name’s photographs. Nourmand generously gave Name and James complete creative control of the edit, design and materials used to create the book. All of Name’s original photographic negatives had gone missing years earlier after Name loaned his film and most of his archive to a former agent who offered to scan the film but somehow lost possession of the material. Because of the loss of his film, tracking down Name’s images for the book proved to be an enormously difficult task. Dagon James and Anastasia Rygle (now James) conducted hundreds of hours of oral histories and scoured archives and collections globally for Name’s photographs, and with Name, collaboratively dated and identified all of the photographs published in the book.

Billy Name’s vintage photographs, negatives and physical archive remain missing and we encourage whoever is in possession of his archive to contact the estate so that we may reasonably negotiate the return of Name’s life’s work.

"I guess I found my future through Billy Name's eye. I saw his pictures of the Warhol Factory when I was in college and I thought, oh that's the place to get to. Everyone is so beautiful and it looks brilliant and complicated-art, music, film, but most of all a kind of wild life. It looked like the future as I imagined it." – Glenn O'Brien, from his introduction to Billy Name: The Silver Age.

Gerard Malanga described The Silver Age as, “the most important book about Warhol.” At 448-pages it is the most comprehensive account of the 1960s as experienced by Billy Name and the people who knew him. The book was launched in November 2014 at New York City’s MILK Gallery alongside an exhibition curated by James and Rygle which was the largest exhibition of Name’s photographs ever organized. More than 100 photographs and objects were on view alongside some of Warhol’s movies featuring Name including Hairicut #2 and two Screen Tests. The opening reception was attended by nearly two thousand people who waited in line to meet Name and see his photographs up close, many of which were exhibited for the first time.

(Left) Name with his 1965 portrait of Edie Sedgwick. (Right) Name making final preparations for his exhibition at MILK with Tony Nourmand, Dagon James, and Anastasia (Rygle) James, 2014. Photos: Courtesy and © Michael Zagaris

Billy Name passed away on July 18, 2016.

Dagon James and Anastasia Rygle married in November 2015 and exactly six months to the day from Name’s passing, their son Winter was born. It was through Name that the couple met and as a tribute to him they named their son after him, Winter William James.

Billy Name appointed Dagon James as his heir and executor to continue the work they started together years earlier. Name gave James detailed instructions regarding how his life’s work should be preserved and presented and spent years meticulously training James how to reproduce and print of his photographs.

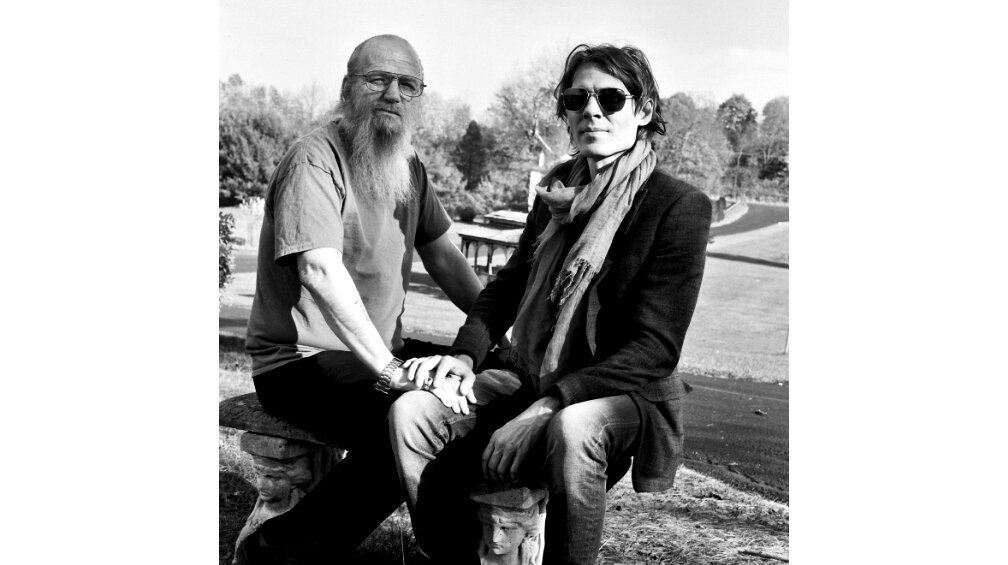

Billy Name and Dagon James, 2014. Photo: Courtesy and © Hunter Barnes.

Much of the information and many of the quotes in this biography were compiled from oral histories and extensive research conducted by Anastasia and Dagon James. They are grateful for the scholarship of many individuals: in particular, Steven Watson, specifically his 2003 book Factory Made: Warhol and the Sixties (Watson page numbers above reference this publication) and Gary Comenas who runs WarholStars.org who have thoughtfully, accurately, and respectfully written about Billy Name in their respective publication and who Name thought very highly of. The James’ would also like to acknowledge the scholarship and research of all of the individuals at the Andy Warhol Film Project, specifically Callie Angell and Claire Henry and current and former employees of The Andy Warhol Museum including Matt Wrbican, Matt Gray, Greg Pierce, Greg Burchard, and Eric Shiner. The James’ would also like to express their gratitude to everyone who over the years have opened their archives and shared their memories of Name including Gerard Malanga, John Cale, Glenn O’ Brien, Gillian McCain, Brigid Berlin, Bibbe Hansen, Sean Carillo, Diane di Prima, Neil Printz, Vincent Fremont, Shelly Fremont, Danny Fields, Robert Heide, Allen Midgette, Viva, and Mary Woronov.